Holger Sambale (22.06.2022):

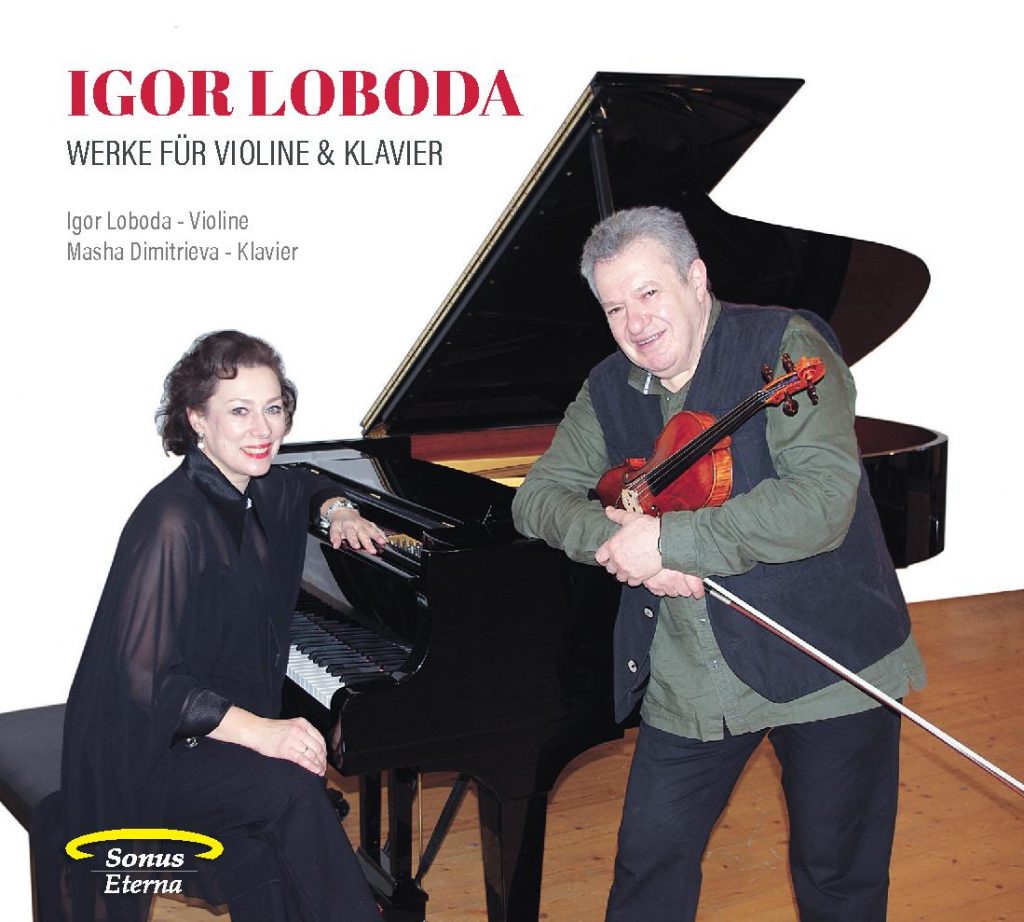

If one has encountered the name Igor Loboda before, it is probably most likely in connection with the Georgian Chamber Orchestra Ingolstadt, the former State Georgian Chamber Orchestra, which emigrated in toto from the then still existing Soviet Union in 1990 and has been based in Ingolstadt ever since. Loboda, born in 1956, plays there in the second violins, but is also an extremely productive composer and has already appeared twice on CD productions of the chamber orchestra with his own works. This new release from the Sonus Eterna label, which presents works for violin and piano (although both instruments are not always involved at the same time), is the first album devoted entirely to his compositions.

Neoclassicism, folklore and jazz influences

The most weighty work on the CD is Loboda’s Violin Sonata (or Sonata-Fantasia) No. 2, written as late as 2021, which provides a good guide to the basic stylistic coordinates of his music. Neoclassical tendencies (see, for example, the striding bass figures of the middle section in the style of a baroque aria) meet Georgian folklore and jazz influences, the latter, among other things, in the form of rhythmic figures such as 3+3+2 quavers and blues-like harmonic reversals, usually (and especially in this work), however, nowhere near as prominent as, for example, in Nikolai Kapustin’s work. One of the sonata’s central motifs, the eighth-note sequence g-g-as-g-b-g-as-g, which incidentally also occurs in a similar way in the Fantasie Latino Sempre and seems quite characteristic of Loboda’s melos as a whole, also brings Shostakovich to mind. Well-made, cleanly crafted music that also betrays Loboda’s rock-solid compositional training with such little-known but thoroughly competent composers in this country as Alexander Shaversashvili and Vladimir Cytovich.

Wide stylistic palette

Similar to the Sonata written in more recent times, the Etudes-Tableaux Nos. 1-5 for piano, are part of a cycle (probably still in progress) of 24 such etudes. Concise, concentrated miniatures in which Loboda sometimes explores the limits of tonality more than in the other pieces on this CD. The other extreme is represented in particular by the three concluding pieces, in which influences of jazz, Latin American dances and light music dominate. In Katzentanz, for example – the only work for solo violin on this CD – the violinist accompanies himself through all sorts of rhythmic hissing and snapping noises, a work, incidentally, that has apparently also found use in school music and whose mere minute and a half betrays Loboda’s sense of the right dimensions; he does not overdo his effects. The composer’s Georgian roots are particularly evident in the piano piece Tbilisoba, which is reminiscent of corresponding miniatures by Balanchivadze or Taktakishvili, for example. Charming is Der Walzer in 4 for piano, a waltz written in 4/4 time, whereby the additional quarter is to be understood as a retarding moment, as a composed hesitation.

Excellent advocate of Loboda’s music

Loboda has found an excellent advocate for his music in the pianist Masha Dimitrieva. She is always able to realize the characteristics of his miniatures, which vary from piece to piece. Loboda himself can be heard on the violin, which gives these recordings a special seal of authenticity. The booklet presents Loboda and his works in detail, but here and there some editing would have done the text good (the Boueles-Saal will surely be the Boulez-Saal etc.). Unfortunately, the track list and lyrics do not always clearly indicate the instrumentation of the individual pieces. All in all, Loboda is to be experienced here as a versatile, technically sovereign and often humorous composer. I would certainly not go as far as Franz Hummel (himself a composer, as we know), who even calls Loboda one of the “most imaginative composers in Europe”, but there is enough room for listening beyond all superlatives, and Loboda’s music is unquestionably to be found here.